Title art by Laura Gilmore.

An Informative Analysis on the Evolution of Clickbait in Reporting

Every internet user has likely fallen victim to clickbait posing as news. Quick, catchy, emotional headlines (usually less than 140 characters) that make the content enticing. Often times, the content of the webpage is not what the headline implied. People accuse media sites such as Upworthy or Buzzfeed as the biggest culprits of clickbait, however it is not a problem isolated to a few websites, it has spread through most of online media.

The Shocking Truth About Clickbait

To further understand how news outlets use clickbait to propagate their biases, it must be defined. Many internet users use the term as a categorical statement for listicles and other low-quality content. Another definition could be any headline or post aimed at tricking or enticing a user to click. However this is not accurate enough; enticing readers has been the purpose of headlines since the beginning of newspapers. A better way to define clickbait is to view it through the eyes of then, Vox Acting Managing Editor; now, Editor-in-Chief of The Verge, Nilay Patel in a 2014 interview with Andrew Beajon of Poynter, “Most clickbait is disappointing because it’s a promise of value that isn’t met…” (Poynter). This is the first characteristic of clickbait: a title that over-promises. Writers accomplish this by making vague, generalized, catchy statements.

Another common characteristic is forward-referential language in the headline or social media post advertising the attached story. There are two different kinds of forward-referential language, discourse deixis and cataphora. Discourse deixis is language that refers to the subject of the article while the headline lacks greater context to make it understandable. For example, “This is the reason this essay should be shared.” The word “this” requires context that is not stated in the headline. In order to understand why this paper should be shared, you would be forced to read the content of the essay and discover the reasons laid out in the body of the text. Cataphors refer to context-providing content that occurs later within the text. “He was so impressed with the quality of the essay, the reader shared it on social media.” In this example, “he” is the cataphor; it refers to the reader—the context—later in the same text. Forward-referential language typically uses pronouns, adverbs, and articles. However, they may also use imperatives, interrogatives, or general nouns that require context provided in the article. The information on forward-referential language comes from an article in the Journal of Pragmatics vol. 76 entitled, “Click bait: Forward-reference as lure in online news headlines.” This article analyzed forward-referential language within Danish news headlines. The author does disclose a limitation; different kinds of forward-referential language are expressed in different ways depending on language and cultural settings. Despite that limitation, all languages have demonstrative forms of speech, therefore forward-reference is possible regardless of language.

A third component of clickbait is sensationalism. Katarzyna Molek-Kozakowska said about sensationalism, “Understood here as a discourse strategy of ‘packaging’ information in news headlines in such a way that items are presented as more interesting, extraordinary and relevant than might be the case.” In her article, Molek-Kozakowska explains the two parts of sensationalism, sensationalist content and sensationalizing content (Molek-Kozakowska 2013). Stories involving scandal are sensationalist by nature but it is still possible to sensationalize these. How the news reported the death toll during the Iraq War makes this evident. In 2007, NBC News ran the headline, “2007 was the deadliest year for U.S. troops in Iraq.” The article states early on that 899 troops were killed that year. However that number pales in comparison to the deadliest years of previous wars. The deadliest year of the Vietnam War was 1968 with 31,000 U.S. deaths (“Bloodiest Year of the War Ends”). The truth is, the Iraq-Afghanistan War is the 9th deadliest war in American history—only more deadly than the Spanish-American War and the Gulf War (civilwar.org). The NBC News story was accompanied by a video showing explosions and violence to support that 2007 was a tragic year for the American war effort. This is one of many examples from that era sensationalizing an already sensational story.

Understanding the anatomy of clickbait is important to identifying it. A clickbait headline can contain all or just one of the above components—over-promising text, forward-referential language, and sensationalism. So, for the sake of this paper, the definition of clickbait will be: An intentionally vague, often forward referential, headline or social media copy which sometimes uses sensational language or imagery, aimed at enticing users to click to a story that fails to deliver on its promise. Working with this definition, this paper will analyze the historical contributions of journalistic practices similar to clickbait.

The Unbelievable Way Clickbait Works

It’s nice to believe our desire to read an article on the internet is harder to manipulate than it is. However, it’s all rooted in simple psychology—the psychology of curiosity. Best explained in the information gap theory, by George Loewenstein, “A form of cognitively induced deprivation that arises from the perception of a gap in knowledge or understanding.” Basically, the difference between what one knows and what one desires to know. This gap is the primary motivator behind why internet users have a hard time resisting clickbait, even when they are media-literate users. Phrases like “You’ll never believe…” and “After this your opinion of … will be changed” are examples of types of headlines that create an information gap.

This is How it All Began

To think of clickbait as a journalistic problem unique to the 21st century would be incorrect. Using the previously mentioned definition, it would be remiss to not mention yellow journalism, from which clickbait descended. According to the United States Department of State Office of the Historian, “Yellow journalism was a style of newspaper reporting that emphasized sensationalism over facts.” Popular in the late 1800s, this journalistic style served as a catalyst for the Spanish-American War (Department of State).

Joseph Pulitzer, owner of The New York World, and William Randolph Hearst, owner of The New York Journal, were competing for newspaper sales. In a marketing ploy, these publishers began using sensational headlines and would misreport or exaggerate the news. The goal was to frighten the reader and invest them “with the plight of a supposedunderdog.” No event better encapsulated these practices than the sinking of the USS Maine in 1898. The overdramatic and post-truth reporting—blaming Spain for the attack without evidence—is credited with drumming up public support to encourage McKinley to declare war. After this, Hearst is quoted, “You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war!” (Big Think). The image to the left was the front page of the New York Journal after the sinking of the USS Maine. Even as early as the 1890s you can see information gap theory being employed along with sensationalism to sell papers. Using “an Enemy” instead of “the Spanish” begs the question, “who is America’s enemy.” Well, the only way to find out is by reading the article. In addition the large font and the exorbitant reward offer add sensationalism to the equation.

These Weapons Aren’t Unique to the News

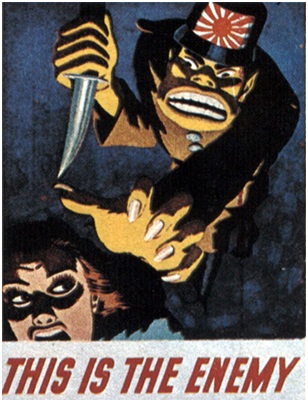

In an effort to generate support for World War II, propagandists used similar tactics as yellow journalists. Some of their media would use forward-referential language and sensational imagery (especially when characterizing race) to encourage certain actions. “This is the enemy” is a clear example of this. The simple text, read out of context, would not inform the reader of who the enemy is. The racist caricature of a Japanese man grabbing a young, white woman serves as the sensationalist image to incite fear towards those ofJapanese descent. With these features in mind and the actions people took towards the Japanese during WWII, the goal of propaganda was achieved—“to influence people psychologically in order to alter social perceptions” (Missouri). Propaganda only works if it is read; therefore using tactics similar to clickbait makes sense when viewed through the lens of the goal stated above.

Why was Vietnam Reported This Way?

Misleading reporting didn’t end with the 19th-century, but continued to flourish throughout the conflicts of the 20th century. Richard Nixon is quoted, “No event in American history is more misunderstood than the Vietnam War. It was misreported then, and it is misremembered now.” Yellow journalism and practices of clickbait are not exclusive to print or online media as was made clear during the Vietnam War. In the 1960s, television became mass media and for the first time, Americans could experience the atrocities of war from their living rooms. In an effort to maintain viewership, broadcasters displayed the inhumanity and brutality of Vietnam; and by doing so, shaped public opinion against the administration. The atrocities displayed every night on television and written about in the papers were not unlike those experienced in previous conflicts of the 1900s. Along with the chosen imagery of the war, the media also failed to provide context as to why America had to enter the conflict. The war was a result of a communism containment policy, which was necessary to prevent the growing ideology throughout southeast Asia.

Looking at the front cover of The Sun is a prime example of poor context—thus creating a curiosity gap—and sensationalism in media reporting during Vietnam. The main image only shows children crying and running away from soldiers. What are they running from? American soldiers or something worse? What exactly is the horror? All we know is that there is a bombing, but which bombing in particular? These questions combined with the emotions triggered by the sensational photograph of a naked child crying contributes to the reader’s desire to purchase this magazine.

What Does a Child Have to do With War?

At the end of the day, the media is only as powerful as the information it has. In no conflict prior was this truer than with Operation Desert Storm. After the mistakes from Vietnam, the Department of Defense employed strict regulations on the press when reporting about Desert Storm. This gave the military “a virtual monopoly on media coverage. (Edge)” Manipulation by the U.S. military isn’t the only way that the media and the American people were deceived. Before the war, the Kuwaiti government launched a multi-million dollar public relations campaign using numerous PR, law, and lobby firms. On top of this, the largest of these firms, Hill & Knowlton, had Craig Fuller at the helm of its Washington office. Fuller was one of President Bush’s friends and political advisors. All the propaganda H&K created in support of its client paled in comparison to the fictional account of Nayirah at a congressional hearing. A 15-year-old girl, claiming to be a volunteer at a hospital, told the story of Iraqi soldiers killing babies in a hospital in Kuwait City. Many argued that this emotional testimony is what drummed up the most support from Americans (prwatch.org). With this scenario, it is hard to blame the media for misleading the public or even accuse them of being yellow journalists who only care about selling papers, but the fact remains that with sensational stories like Nayirah’s, the media had no choice but to report sensational headlines.

This Explains All You Need to Know about 2016

What sets clickbait apart from the headlines of yellow journalism is the technology. Before, sensational headlines and misreporting were relatively confined to their geographic regions, however with the dawn of social media, geography was no longer a restriction. These highly shareable, misleading, sensational stories contribute to the culture of “post-truth politics”—a word so popularly used in 2016, it earned a place as “word of the year” in the Oxford English Dictionary. It is defined as, “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief” (Washington Post). With thousands of different media outlets vying for attention, clickbait has become, in some instances, a first-resort when reporting the news. This is what gave rise to “fake news,” the seeming rise of white nationalism culminating with the unpredictable victory of Donald Trump. The story of Paris Wade and Ben Goldman exemplify the power these tactics have had on the 2016 news cycle. Founders and writers of LibertyWritersNews.com, Wade and Goldman have tapped into the power of clickbait to create sensational lies and mistruths about Democrats, theDemocratic Party, and progressive movements. The sensational tactics they used targeted right-wing people’s fear and anger towards the Obama administration, Hillary Clinton, and the establishment. Headlines like, “Look At Sick Thing He Just Did To STAB Trump In The Back” are commonly used to report “all opinion, innuendo, and rumor” (WaPo). These headlines work because of the enormous information gap that is created coupled with extra-sensational language and syntax. Aside from baseless accusations against democratic party leaders for funding or supporting terrorist organizations, Liberty Writers News does not frequently cover international conflict or topics of war.

Clearly, the essence of clickbait—sensational, post-truth content—is not new to the mainstream press. So, why is clickbait such a pejorative term in the 21st century? Arguably, because of the earlier media sites that have dominated people’s news feeds and timelines like Buzzfeed and Upworthy and the recent hijacking by post-truth writers on the fringes of the political spectrum. In order to compete for ad revenue, more traditional media sources like The New York Times and The Washington Post have been forced to adopt to these tools. In How the Times have Changed for the Washington Post, Jack Murtha describes The Post as “Woodward and Bernstein meets Buzzfeed.” Murtha explains how the new digital focus at The Post has led to great success and even, by some metrics, surpassing The Times. Despite The Post’s success with clickbait, he explains there still are vocal critics. Murtha identifies the following two tweets as examples of such:

@washingtonpost Click bait. Is this the same newspaper Woodward and Bernstein worked at?

— burble2 (@Burble2) November 8, 2015

@washingtonpost Stop with the click bait headlines!!!

— Molly Ariotti (@mollyshewrote) September 26, 2015

Both of these tweets were quick to be pointed out by followers as clickbait; but only one of these is such. Although the first tweet has the structural components of clickbait, it asks a question and incites curiosity in the reader, the headline is in no way vague or misleading. The content of the article itself is highly educational and well-written. The second tweet, however, is clickbait. The article is about the pope’s entire visit to the U.S. and, although the pope did see a boy with cerebral palsy, all he did was bless the child. No miracle occurred; the child was not cured. However, The Post intentionally leaves a wide curiosity gap that is never satisfied—it promised a value that was never met. Murtha does point out the term “clickbait” is subjective and does not claim that one or the other is clickbait.

The Amazing Conclusion About Clickbait

It is easy, as a reader with decent media literacy, to view clickbait as the shortcoming of journalism in the 21st century. However, tracking its evolution through history, it is clear that the prevalence of the business mindset as opposed to a journalistic one isn’t new. Because of yellow journalism, the media has had exceptional power to shape public opinion—especially with regard to war. The question, however, still remains: is clickbait bad? The short answer is no. It is simply another means to an end. Today it’s difficult for even the most popular media outlets to be heard over the noise of thousands of other options available on the internet and the news still needs to be heard. Because of this, sources like The Post and The Times have had to adapt and use all the tools available. Using vague headlines creates curiosity in the reader that can only be satisfied by reading the story. This thirst for information can be invaluable when educating the public on war or politics.

However, it can also be abused. It can mislead and deceive the public to advance a less-than-righteous agenda. Despite public opinion, the elements that make up clickbait—vagueness; forward-referential language; and sensationalism—are not inherently bad. Using these kinds of headlines to encourage the people to read an important story, is valuable to an informed citizenry and thus, democracy. However, the danger comes when the information gap generated by the headline exceeds what the story fills and the reader is forced to draw his/her conclusions based upon any remaining sensational information. When not used appropriately, or when used with sinister intentions, these same tools can shape public opinion and lead to misinformed policies or, even worse, war.

Understanding clickbait as simply a weapon available in a journalist’s arsenal and not as a plague on journalism can empower the reader. Having the knowledge of clickbait anatomy will allow you to sort through the lower-quality content and find the real stories. Excessive sensationalism is the first clue; the more sensational, the less likely it is grounded in truth. Vagueness will always be present in headlines, and the information gap is necessary for news outlets to maintain readership, but there is a difference between leaving out details for the sake of mystery and leaving out details necessary for context. Finally, forward-referential language will continue to appear in the news and is often used in non-clickbait headlines, to filter content based off of this parameter would remove most valuable stories as well. However, acknowledging the practice of forward-referential language will still help you identify potential clickbait articles. Simple awareness to these three characteristics are the best way to combat clickbait and prevent it from deceiving you.

As this practice grows in all facets of the media, it will be interesting to watch how clickbait continues to affect public opinion especially if America is forced to enter war. We’ve historically seen how the characteristics of clickbait can influence opinion, especially with regardto the Spanish-American War and the Vietnam War; with modern technology, only time will tell the power that clickbait will have in future war journalism.

Works CIted

Associated Press (2007, December 31). 2007 was deadliest year for U.S. troops in Iraq. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://www.nbcnews.com/id/22451069/ns/world_news-mideast_n_africa/t/was-deadliest-year-us-troops-iraq/

Beaujon, A. (2014). The real problem with clickbait. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://www.poynter.org/2014/the-real-problem-with-clickbait/258985/

Blom, J. N., & Hansen, K. R. (2015). Click bait: Forward-reference as lure in online news headlines. Journal of Pragmatics, 76, 87-100. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2014.11.010

Bloodiest year of the war ends. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/bloodiest-year-of-the-war-ends

Civil War Casualties. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://www.civilwar.org/education/civil-war-casualties.html

Hehman, M. G., Wiener, B., Hunter, A., Harmon, S., & Bonzon, C. (n.d.). 100 Years of War and the Media..An analytical evaluation of the role media palayed in 5 major American Wars. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297c/war_peace/media/hmedia.html

How PR Sold the War in the Persian Gulf. (2013). Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://www.prwatch.org/books/tsigfy10.html

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 75-98. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.116.1.75

McCoy, T. (2016, November 20). For the 'new yellow journalists,' opportunity comes in clicks and bucks. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/for-the-new-yellow-journalists-opportunity-comes-in-clicks-and-bucks/2016/11/20/d58d036c-adbf-11e6-8b45-f8e493f06fcd_story.html

McNeal, M. (n.d.). One Writer Explored the Marketing Science Behind Clickbait. You'll Never Believe What She Found Out. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from https://www.ama.org/publications/MarketingInsights/Pages/one-writer-explored-the-marketing-science-behind-clickbait.aspx

Miles, H. (n.d.). WWII Propaganda: The Influence of Racism – Artifacts Journal - University of Missouri. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from https://artifactsjournal.missouri.edu/2012/03/wwii-propaganda-the-influence-of-racism/

Milestones: 1866–1898 - Office of the Historian. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2016, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/yellow-journalism

Molek-Kozakowska, K. (2013). Towards a pragma-linguistic framework for the study of sensationalism in news headlines. Discourse & Communication, 7(2), 173-197. doi:10.1177/1750481312471668

Murtha, J. (2015, December 1). How the times have changed for The Washington Post. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://www.cjr.org/analysis/washington_post_vs_new_york_times.php

Ratner, P. (2016, November, 15). Steve Bannon's Rise Caps the Triumph of. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from http://bigthink.com/paul-ratner/last-time-yellow-journalism-was-so-rampant-the-us-got-two-wars

[The Sun Cover Page]. (1972, June 12). Retrieved November 26, 2016.

Wang, A. B. (2016, November 16). ‘Post-truth’ named 2016 word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved November 26, 2016, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/11/16/post-truth-named-2016-word-of-the-year-by-oxford-dictionaries/